What happens when AAA ambitions outgrow economic reality?

The ceremonial quiet period that precedes every earnings cycle offers a moment for reflection on some of the underlying economics in the business of games.

First, and most personally, I spent some time over the weekend analyzing the behavior of my now 15,000-strong subscriber base. What started as a quick monthly digest has spun into a more ambitious project. You’ll notice a few changes in the coming weeks as I optimize the newsletter. Burrowing through the numbers, one thing became clear: I deeply appreciate your willingness to take me seriously, especially when I’m off the mark. Like my classroom, writing in public presents an incredible educational experience.

I’m grateful. Thank you.

Second, I wanted to explore the economics of AAA game development in greater depth. Although not a new topic, it remains poorly understood due to the scarcity of reliable data. Publishers typically keep development costs opaque unless revealing them serves a marketing purpose. This lack of transparency has normalized escalating budgets without meaningful explanations for the underlying drivers of cost inflation.

Considering that ever-increasing development costs fundamentally shape the survival or failure of studios, a deeper understanding of these dynamics is critical to industry analysis.

On to this week’s update.

BIG READ: Gaming’s billion-dollar gamble

The short: Examining the economic fundamentals of contemporary AAA development reveals a potentially unsustainable cost structure that presents material strategic challenges to existing publisher business models.

Amidst the now-repetitive news that everything is about to get more expensive, the games industry is facing its own existential moment. Sure enough, exogenous circumstances like looming tariffs are real and may yet catalyze digitalization. But the underlying endogenous problems, most recently pointed out by Matt Ball here, are just as material.

AAA game development has entered a danger zone where content bloat, not innovation, drives costs to unprecedented heights. Major publishers like Activision, Sony, and Microsoft now regularly spend between $250 and $600 million on a single game production, creating an exclusionary environment where only the wealthiest studios can compete at the highest level.

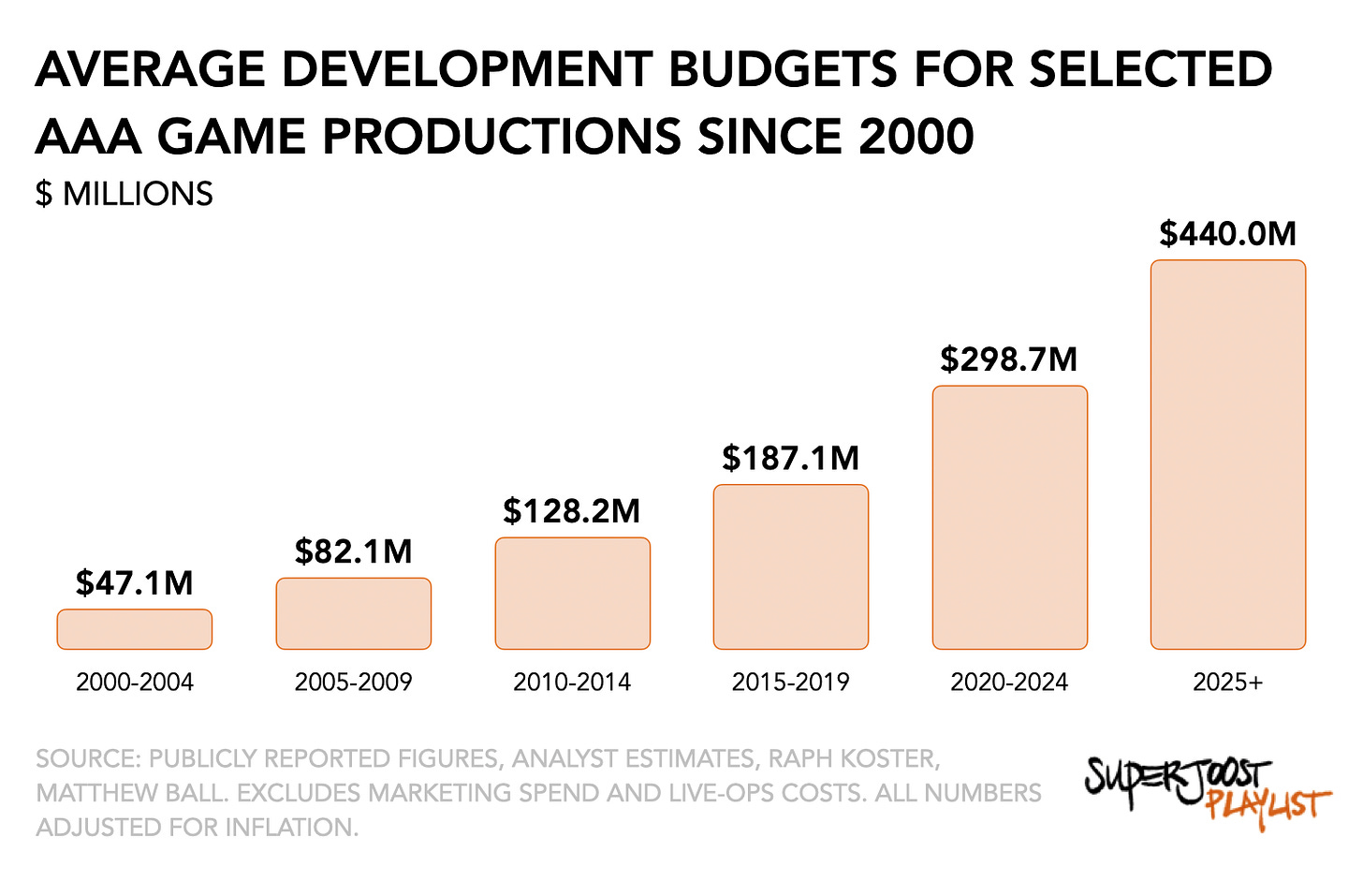

Based on publicly reported development budgets, financial analyst estimates, and a few previous analyses, I cobbled together an approximate average for AAA development budgets. While not perfect, I believe it to be directionally correct.

What immediately stands out, beyond the 8x increase of average development budgets since 2000, is the accelerating slope of the curve.

Numbers associated with recent and near-term releases suggest we’re careening toward the first billion-dollar video game in terms of legacy franchises—a milestone that should terrify rather than excite industry executives. Quick math suggests that Grand Theft Auto VI is costing around $1 billion, excluding marketing and live services costs, representing a 4x increase from its 2013 predecessor. It helps explain why its upcoming release is eyeing the $100 price threshold.

The economics behind these numbers also reveal a fundamental market dysfunction.

When Call of Duty: Modern Warfare cost $80 million in 2009, it represented an ambitious but manageable investment. Today’s Black Ops 6 at $638 million requires a mathematical impossibility—either selling to practically every console owner or charging substantially more than the market will bear. As Raph Koster observed nearly two decades ago, publishers’ obsession with spectacle over innovation has resulted in an increasingly unsustainable trajectory.

What’s driving this cost explosion?

In a word: bytes. The relentless expansion of game file sizes correlates directly with budget inflation. Every additional gigabyte demands thousands of artist-hours creating higher-resolution textures, more elaborate environments, and increasingly photorealistic character models. Yet the efficiency gains from development tools have plateaued since the widespread adoption of engines like Unreal and Unity, leaving studios manually crafting ever-larger experiences without corresponding productivity improvements.

In a 2005 talk titled “Moore’s Wall,” Koster analyzed how the exponential growth in computing power has paradoxically created massive challenges for game developers rather than simply unlocking new creative opportunities. He outlines that while game budgets grew from under $1 million in the early 1990s to over $12 million by 2005—a 22x increase adjusted for inflation—gameplay complexity remained relatively stagnant.

The primary consequence of technological advancement has not been innovation in game mechanics, but rather escalating production demands, particularly in art, sound, and network infrastructure. Koster warned that the cost of creating static assets and maintaining persistent online environments is now outpacing the ability to monetize them efficiently, especially as online games face two to three times higher development costs than traditional AAA titles. Despite the promise of better tools and faster processors, the industry’s economic model is approaching a breaking point. It is part of the reason why developers started pivoting toward more sustainable design strategies, such as procedural content generation, user-driven creativity, and more dynamic use of runtime databases. His argument reminds us that scale alone does not guarantee sustainable growth in industries driven by rapid technological progress—structure and process innovation become essential. (Regular readers will note that this echoes my Play Pendulum theory.)

This trend creates a troubling paradox: as development costs rise exponentially, the audience’s willingness to pay remains relatively fixed. The $60-70 price point has barely budged despite inflation, forcing publishers to compensate through increasingly aggressive monetization schemes. Battle passes, cosmetic micro-transactions, and controversial loot boxes aren’t emerging from corporate greed alone—they’re symptoms of a broken economic model where traditional pricing can no longer sustain production costs.

When it comes to AAA development, Electronic Arts (EA) and Take-Two offer two distinct financial strategies shaped by how they build and monetize their games. EA runs a more systematized model, focusing on annual sports franchises like EA Sports FC and Madden, which not only release reliably each year but also generate high-margin recurring revenue through in-game purchases like Ultimate Team. This approach helps EA keep development costs relatively efficient as a percentage of its AAA bookings.

Take-Two, meanwhile, leans on fewer, content-heavy titles like GTA Online that require much larger up-front investments in assets, cutscenes, and live service features. Over the past decade, EA’s development costs have steadily increased from the mid-20% range to the mid-30% range of bookings, partly due to how it accounts for expenses (recording them as they happen rather than deferring them). Take-Two smooths its numbers by capitalizing development costs and recognizing them when the game launches—but beneath that accounting, the pressure is similar. As budgets grow and timelines stretch, both companies face a tough reality: making AAA games is getting riskier and more expensive, making operational efficiency and monetization strategy more important than ever.

The logic behind these massive investments, however, is sound. When it comes to entertainment, the best bet is often to go all in.

Harvard Business School Professor Anita Elberse’s book Blockbusters argues that in a world drowning in content with fractured audiences, the best way to win in entertainment isn’t to spread your bets but to bet big and loud on a few massive, tentpole projects. Rather than diversifying across numerous tiny efforts, top firms concentrate resources (money, marketing, talent) on potential mega-hits. A successful blockbuster delivers disproportionate returns: it commands attention in an oversaturated market, creates lucrative downstream revenue (sequels, merchandise, spin-offs), and anchors entire corporate ecosystems (Disney’s Marvel Cinematic Universe being the platinum example).

It’s a paradox that feels counterintuitive at first—shouldn’t a wider portfolio reduce risk?—but in reality, the blockbuster strategy thrives precisely because media consumption is increasingly a winner-take-all game, and human psychology favors the familiar, the communal, and the spectacular.

“Contrary to the conventional wisdom that spreading risks across a wide portfolio is the safest strategy, betting heavily on a small number of titles is not reckless — it is, in fact, the surest path to commercial success in entertainment.” —Anita Elberse

It partially explains the many sell-offs we’ve seen in recent months as large publishers focus their portfolios and resources on a small subset of titles with large potential.

Can AI save the day?

Ah, yes, but this is where AI is going to make a huge difference. Well, maybe. Large publishers are already exploring ways to leverage generative AI to offset some of the more mundane activities involved in game development. Quality assurance, for instance, where you drive every vehicle into every wall and report on buggy instances, is an obvious area where AI can shine.

But here’s where the cost of development, the value of intellectual property, and the lack of security around AI exacerbate the risk profile. For one, no legacy publisher will open up their original artwork or intellectual property to an AI provider because the consequences remain unclear. Elsewhere in gaming, Ziff Davis, which owns several notable gaming publications including IGN, Eurogamer, and VG247, is suing OpenAI. It argues that ChatGPT has illegally lifted its writers’ work and now claims it as its own. (For more on this, check Stephen Totilo’s write-up.)

The widespread concerns about intellectual property risks (59%) and unreliable outputs (50%) highlight why such reinvestment is more about cautious experimentation than aggressive cost-cutting, underscoring that the GenAI opportunity is still wrapped in legal red tape and technical growing pains. A 2023 survey found that “few publishers expect development budgets to decrease, suggesting that GenAI savings will help fund bigger, better games.” Despite potential productivity gains from AI, the overwhelming majority of AAA (65%), AA (75%), and indie (57%) publishers plan to keep their development budgets unchanged. Rather than reducing costs, most intend to reinvest any savings into producing bigger, potentially more ambitious games. For now, GenAI promises to make bigger games—but not cheaper ones.

The coming correction

As predicted by Ball, the games industry faces an inevitable correction. The first casualties will be mid-tier studios attempting AAA production values without commensurate resources. Next will come risk aversion, even at the largest publishers, further concentrating investment in established franchises at the expense of creative experimentation. Looking at the shooter category or the slate of upcoming titles, you’ll observe a growing degree of undifferentiated content.

Bigger budgets are no guarantee of success. It suggests that the next wave of innovation needed isn’t about photorealistic textures, high fidelity simulations, or celebrity cameos, but a fundamental rethinking of what creates lasting value in interactive entertainment.

Today’s ballooning budgets have produced a paradoxical creative drought. Publishers can theoretically build anything, but find themselves paralyzed by financial risk and retreating to formulaic franchise extensions instead of genuine innovation. The next gaming revolution won’t come from higher polygon counts, but from studios that rediscover how constraints drive creativity.

PLAY/PASS

Pass. Of all places, Jonathan Haidt appeared on Dutch television to discuss smartphone addiction. Love the work he’s doing. Don’t love his insistence on conflating pornography and games.

Play. GamesBeat is now an independent publication and can finally rest its back from carrying VentureBeat all these years. Congrats, Dean Takahashi!

UP NEXT

Earnings are looking bright, at least for Electronic Arts, with its recent release, Split Fiction, significantly exceeding investor sales expectations by selling well over 3 million copies. As a fan of Hazelight’s other titles, I expect creativity, not content bloat, to win the day.